Originally published in September-October 2004 icon

Maggie Keswick Jencks’ Centres

A View From the Front Line

Since Maggie’s Centres sprang up in Edinburgh, Glasgow and Dundee (Inverness opens this October), Scotland the brave has become Scotland the beacon for cancer caring. Maggie Keswick Jencks, vibrant wife, mother, architect and landscape designer is the woman to thank for that. Ten years ago Maggie had enjoyed five healthy years after breast cancer which then metastasised. High dose chemo and stem cell replacement won her 18 months remission enabling her to live well and create the blueprint for a safe, free, welcoming space where those touched by cancer could wait, draw strength, comfort or information - and, if they wished, explore ways of helping themselves.

In a powerful account of her own experience called A View From the Front Line, Maggie argued that helping yourself - in whichever way you think best can make a powerful difference. But she recognised that choosing your way can be bewildering and exhausting. Says Laura Lee, who was Maggie’s specialist chemo nurse before being appointed Chief Executive for Maggie’s Centres: "The diagnosis of cancer, Maggie felt is a bit like being flung out of a plane with a parachute that may or may not open, and no map when you land behind enemy lines. You needed a mentorship programme - someone to help put together your map which takes into account your personal circumstances and your personal belief system.

Maggie didn’t want to lose the joy of living in the fear of dying

"Maggie didn’t want to lose the joy of living in the fear of dying; she wanted to live with optimism and hope. Yet so often health professionals end up almost forcing harsh realities on people for fear of giving false hope. Doctors rely on statistics as prognostic indicators, but Maggie was interested in the fact that doctors cant know where a particular individual is on the statistical chart. There’s a bell-curve on that chart and Maggie (who took up Qigong and yoga, had weekly reflexology and counselling) was interested in what you can do for yourself that could push the curve out and help ensure that you are the exceptional patient who lives beyond the predicted average.

In Maggie’s view, impersonal hospitals stripped new patients of their hope and miserable waiting areas with institutional strip lighting "could finish you off’. Having her bone marrow transplant in an isolated room looking onto a concrete wall, Maggie knew that you needed a view: just to see clouds moving or a tree - some affirmation of life going on - would make one feel so much better. She never forgot the consultation where she was told (before her year and half’s remission) that she had bone marrow involvement, liver disease and two months to live. Her recollection was that the specialist had scarcely finished telling her not to bother seeking options as nothing could be done, before a nurse was tapping her on the shoulder to indicate that other patients were waiting to be seen. Many patients feel weakened enough without contesting bad hospital experiences. But Maggie saw that hospital environments giving out the message "how you feel is unimportant" could with very little effort and money be transformed into ’Welcome! We are here to reassure you, and your treatment will be good and helpful to you."

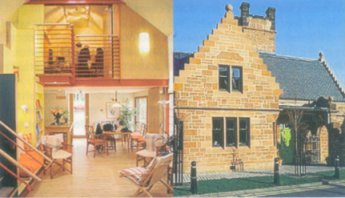

Maggie put her own money where her detailed visionary plans were, so enabling the first Maggie’s Centre to rise from the old stables in a tucked-away corner of Edinburgh’s Western General Hospital. Set behind a pretty strip of cottage garden, this Centre, designed by local city architect Richard Murphy is a bright light, characterful place with big windows and pale wood floors, splashes of dusky pastel paint, homely cushioned sofas and - for those who wish - an information library with internet facility. Every Maggie’s Centre has its own, slightly different programme of relaxation and meditation, creative writing or expressive art. The day icon visits Edinburgh there’s a support group meeting in one pretty sitting area and a nutrition workshop in the other. But the hub of all Maggie’s Centres is the open-plan kitchen with wooden table, and a very well-used kettle:

What’s my life about? What am I here for?

"Some people may just want a cup of tea whilst they read the paper before going off to radiotherapy" says Chief Executive and former oncology nurse specialist Laura Lee, "Some may want to ask about financial benefits - we have someone working here who is expert in that area. Others may want a little gentle confidence coaching in how to ask pressing questions of their consultant or just to air their feelings about what it means to have cancer and how they can talk about it to their children. Some may want to explore deeper philosophical questions: ’What’s my life about? What am I here for?’"

A striking 37 per cent of Maggie’s Centre users are men, and 40 per cent are family and friends. "We have about 70 people a day coming through the Centre and they certainly won’t find a receptionist sitting at a predictable desk." says Laura. ’I think the physical building has a significant impact on the way we work here - people come in and are immediately involved in something normal - like stirring a hot drink. We can sit down with them and listen in a setting that makes them see that their feelings, their questions and desire to do something more are normal. People touched by cancer often talk about loss of control, of feeling isolated, helpless and hopeless. So it’s good to come into a domestic environment that doesn’t feel institutional or scary...

It’s around the kitchen table that teenagers in (or post) treatment for cancer meet monthly to plan cinema trips, white water rafting or just to rap openly with others of the same experience. "They talk very honestly about study issues, how to manage schooling, college or uni, family issues, relationships, going out, partying says group leader Andrew Anderson "about all the stuff that teenagers should be doing, but find intensely affected by their condition. The group’s very much about encouraging the power of thinking not ’Cancer is my life’ but ’My life needs to continue, so how can I accommodate cancer and make it only a part of my life.’" "Sometimes," says Laura "people may want to talk and unburden and cry and we’ve noticed that even in this very open space they do feel free to show their feelings. Nobody has ever protested lack of privacy here, though paradoxically they complain about it all the time in hospital."

"People here understand" said Harry Coldman, visiting the Centre as his wife Lucy’s carer. They have a darn good idea what you’re going through." Says Laura "When Maggie started her chemo here at the Western General, her direction was not so much along the lines of ’What shall I do?’ as ’Actually I’m well educated and well-resourced and I still find this bloody difficult in terms of making choices and decisions.’"

To recover from the bone marrow transplant Maggie flew out to LA where her husband (the eminent architect Charles Jencks) had taken a house during a visiting lectureship. She started looking around at what the Americans offered in terms of help and support and came back with the outline concept of a centre where people could come and put their personal map together. "So we formed a little project group here in the hospital" Laura explains "and we went out looking at what was already available here - not much at the time, apart from the Linda Jackson information Centre at Mount Vernon hospital and the Bristol Centre.

We also went to the States together, and of many different facilities we were particularly struck by the Wellness Community. where the emphasis was lesson information and more on the fighting spirit and helping people be active participants in their fight for recovery. As a nurse I suppose I was used to the idea that there was medicine and there were complementary therapies - two separate approaches. Here people could actually see what was possible without having to choose one or the other"

Maggie died a year before her Edinburgh Centre opened in 1996, but went delightedly to the opera (Simon Bocanegra) two days before and the day before was poring over the architectural plans.

As she died without a will, her vision could well have foundered, "so it was very much down to the goodwill and the commitment of her husband Charlie and her 90 year-old mother that Maggie’s Centres went ahead," says Laura. "They wanted to make her wish happen". You couldn’t fail to see why: her concept has also drawn in some extraordinary talent and energy:

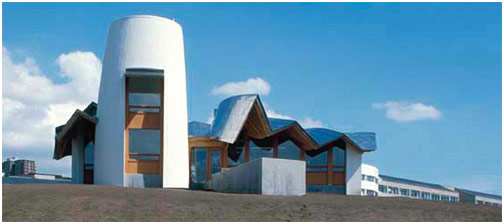

Frank Gehry, famed for his Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao waived his fee for designing the curved walls and concertina-ed steel and timber rooftops of the Dundee Centre (Below).

Sir Bob Geldof, a motorycycling chum of Gehry’s, headed north to open the Centre, which he endearingly immortalised as "A cute little dumpling of a building."

The Inverness building designed by David Page, and landscaped with Charles Jencks’ stunning grass mounds will certainly add the wow factor to the hospital’s towering 1970’s faade.

And soon Maggie’s Centres will head south of the border, responding to approaches from The Charing Cross Hospital, London, from The Churchill, Oxford, from Swansea and from Cheltenham.

"Fundraising is hard work" says Laura "but the five year plan is to have 12 centres built, up and running so we can do what we do well. We’ll open our doors to other innovators who can learn from what we do and take it forward in turn

For more in formation on Maggie’s Centres tel: 0131 537 3121; Website http://www.maggiescentres.org.